Project Midan: Secret Nuclear Testing Sites

Project Midan, meaning "field" in Farsi, emerged as a significant subproject under Iran's Amad Plan, specifically Project 110, with a focus on establishing an underground nuclear test site. This initiative, aimed at testing nuclear explosives, was part of a broader effort to develop nuclear weapons, with the Amad Plan targeting the completion of five warheads by March 17, 2004, including one for underground testing. The project's timeline, starting on December 12, 2000, with an anticipated completion by November 16, 2003, faced delays, achieving only 38% completion by 2002 compared to a planned 46%, as detailed in reports from the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) Project Midan Report.

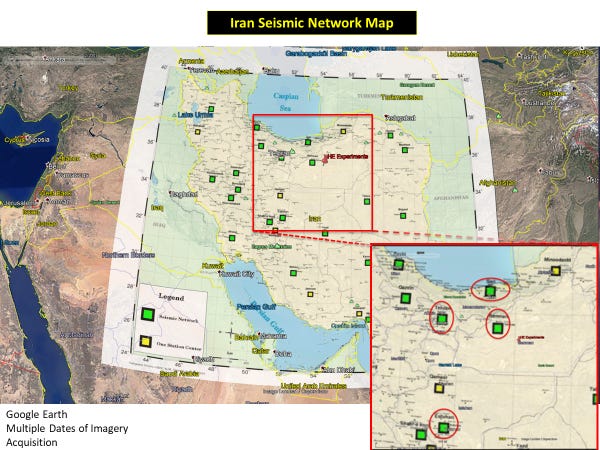

The selection process for test sites was meticulous, involving the identification of five potential locations, documented in the "Site Selection Report" (Abuzar 1, August 2002), which utilized Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for characterization, considering factors like population density, distance to cities, and weather conditions. High explosive tests, crucial for developing seismic yield measurement methods, were conducted in 2003 near the Chah Shirin mountains, close to the Semnan Space Launch Center. These tests, detailed in the ISIS report, included three significant explosions: 0.5 tons on February 6, 2003, and 4.62 tons and 2.15 tons on April 17, 2003, detected by seismic stations up to several hundred kilometers away, such as in Esfahan. The table below summarizes these tests:

These activities were likely located at the Semnan Military Proving Ground, as suggested by geospatial analysis, reinforcing the project's focus on practical testing capabilities.

Project Midan involved significant technical advancements, including the design of a cylindrical metal container (approximately 2 meters long, 1 meter in diameter) and a carrying device for lowering into shafts, with images archived for reference. The project also explored detonation at a distance, testing equipment like Exploding Bridgewire (EBW) firing systems over long distances, such as a 400-meter shaft with a 10-kilometer firing distance. Yield estimation methods were developed, with seismic methods at 30% implementation by 2002, radiochemical at 10%, and hydrodynamic methods just beginning, indicating a comprehensive approach to measuring nuclear explosive yield.

Key personnel involved, as noted in a planning meeting on October 22, 2000, included figures like Dr. Fereydoon Abbasi-Davani, who later headed the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran in 2011, and Dr. Masoud Alimohammadi, assassinated in 2010, alongside others like Brigadier General Mohammed Naderi and Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the Director of the Amad Plan and head of the SPND. Their involvement underscores the project's high-level coordination and expertise.

Despite the official downsizing of the Amad Plan in late 2003, archive information suggests continued nuclear weapons activities, potentially integrated into civilian programs at universities and maintained through separate secret military initiatives. This continuation raises significant concerns regarding Iran's compliance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT, Article II) and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT, signed in 1996 but not ratified), contradicting earlier statements to the IAEA. The ISIS report recommends that the IAEA verify sites, equipment, and personnel, while the CTBTO assesses Iran's testing history, and the U.S. considers sanctions on involved entities.

The exposure of Project Midan came through documents from the Iranian Nuclear Archive, seized and analyzed by ISIS, revealing Iran's intentions and capabilities. Efforts to verify seismic activities, such as searching for records near Semnan in 2003, showed a major earthquake in Kerman but no direct matches for the reported tests, possibly due to their classification as man-made explosions rather than natural seismic events. This aligns with the project's focus on non-nuclear explosive tests for method development, detected locally but not necessarily listed in global earthquake catalogs.

In summary, Project Midan represents a critical, albeit controversial, chapter in Iran's nuclear ambitions, with detailed documentation providing insights into its scope, challenges, and ongoing implications for international nuclear non-proliferation efforts.

Fordow Nuclear Enrichment Plant

The Fordow Enrichment Plant, codenamed Al Ghadir, represents a significant component of Iran's nuclear program, with its history, purpose, and current status reflecting both technical advancements and international scrutiny. This analysis, based on reports from the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS) and associated PDF documents, provides a detailed examination of the facility, leveraging information from the webpage The Fordow Enrichment Plant, aka Al Ghadir and linked resources.

Situated near Qom, Iran, and originally designed as part of the Amad Plan, Fordow is a covert nuclear weapons development program. Its primary purpose was to produce weapon-grade uranium, specifically targeting an output of approximately 45 kilograms per year of weapon-grade uranium hexafluoride. This output translates to roughly 30 kilograms of weapon-grade uranium, sufficient for the production of 1-2 nuclear weapons annually, assuming a requirement of 15-20 kilograms per weapon. The facility's underground location was likely chosen for security and to evade detection, aligning with its strategic military objectives.

Research suggests that construction of the Fordow plant began as early as 2002, a timeline established through geospatial analysis and satellite imagery detailed in the report Al Ghadir Site Report. This evidence, including figures showing construction activities from June 2004, contradicts Iran's official claim to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) that construction started in 2007. The discrepancy has been a point of contention, with the IAEA unable to confirm Iran's chronology, as noted in various IAEA reports linked on the ISIS page, such as IAEA Report Iran 16November2009.

The plant's existence was revealed by Western intelligence agencies in September 2009, prompting Iran to declare it to the IAEA shortly thereafter. This discovery marked a significant escalation in international scrutiny, with reports like Analysis IAEA Report highlighting the implications of Iran's undeclared nuclear activities.

The Fordow plant was designed to house approximately 3,024 IR-1 centrifuges arranged in 18 cascades, capable of enriching uranium to weapon-grade levels. However, it was planned to use low enriched uranium (LEU) as feedstock, rather than natural uranium, indicating a dependency on other enrichment facilities within Iran, such as Natanz, or potentially unsafeguarded foreign supplies. This reliance on LEU feedstock is detailed in annexes like Al Ghadir Annex I, which provide technical insights into the plant's operational design.

Post-2009, under international pressure and as part of negotiations, the plant's purpose was modified. By early 2014, approximately 2,700 IR-1 centrifuges were installed, with 696 of them operational in four cascades to produce uranium enriched to nearly 20% U-235, aligning with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) limits. This modification is documented in reports such as Fordow Update January 2014.

As of the latest reports from March 2019, the Fordow plant operates under the constraints of the JCPOA, with enrichment activities halted. Instead, parts of the facility are utilized for stable isotope separation in collaboration with Russia, as noted in ISIS Analysis IAEA Safeguards Report 14November2013. This shift is significant, as the report emphasizes that there is no credible civilian justification for the plant's existence, raising questions about its continued operation and Iran's compliance with nuclear non-proliferation treaties.

The JCPOA, signed in 2015, aimed to limit Iran's nuclear activities in exchange for sanctions relief, with Fordow specifically restricted to non-weapons-related uses. However, the lack of a clear civilian purpose, as highlighted in Iran's Evolving Breakout Potential, underscores ongoing international concerns.

Controversies and IAEA Concerns

The Fordow plant remains a focal point of controversy, particularly regarding its original intent and the accuracy of Iran's declarations. The IAEA has expressed ongoing concerns, with reports like IAEA Iran Safeguards report 22May2013 noting discrepancies in Iran's timeline and purpose. The Iranian Nuclear Archive, analyzed by ISIS, provides evidence of the plant's military objectives, contradicting Iran's claims of purely civilian intentions, as discussed in Anatomy of Iran's Deception.

This controversy is further complicated by Iran's actions post-2019, particularly following the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA in 2018 and subsequent escalations, though these developments are beyond the scope of the provided 2019 reports. The ongoing debate highlights tensions in international nuclear oversight, with calls for continued IAEA verification and CTBTO assessments.

The report includes detailed figures in annexes, such as Al Ghadir Annex II, which provide visual evidence of the plant's development. These include views of the Qom/Fordow/Ghadir Underground Uranium Enrichment Plant from various angles, showing surface activities like conduit installation and backfilling, dating back to 2004. These images, summarized in the table below, are crucial for understanding the construction timeline and countering Iran's official narrative:

Broader Context and Implications

The Fordow plant's history reflects the complexities of Iran's nuclear program, with its initial military intent, international discovery, and subsequent modifications under global scrutiny. The lack of a credible civilian justification, as noted in multiple ISIS reports, aligns with broader concerns about Iran's compliance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT). The ongoing debates, fueled by archival evidence and IAEA reports, underscore the need for continued monitoring and diplomatic engagement.

In summary, the Fordow Enrichment Plant, originally designed for weapon-grade uranium production, has been repurposed under international agreements but remains a symbol of contention in global nuclear non-proliferation efforts, with its history and current status reflecting the delicate balance between national sovereignty and international security.

Sources: