The Haversack Ruse

A Military Intelligence Operation of Acting, Deception, and Misdirection

The Haversack Ruse stands as a fascinating example of military intelligence schemes of deception during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I, particularly during the Third Battle of Gaza in October 1917. This operation, while celebrated for its ingenuity, is also shrouded in controversy.

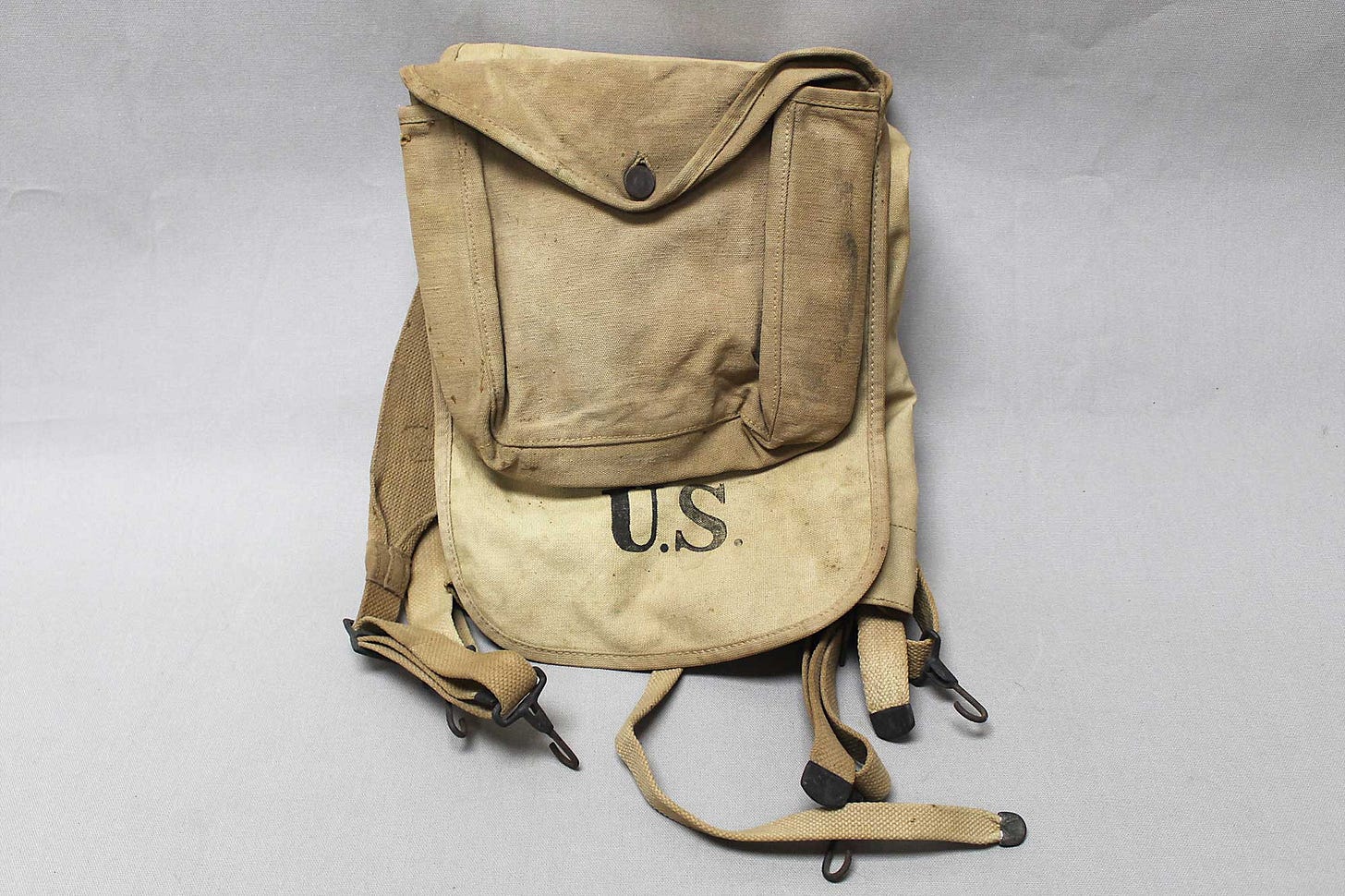

The Sinai and Palestine Campaign was a critical theater of World War I. British forces, under General Sir Edmund Allenby, sought to push back Ottoman control in the region. After two failed attempts to take Gaza in 1917, the Haversack Ruse was conceived as part of a broader strategy to break the stalemate. The operation involved the intentional loss of a haversack, a type of bag often used by soldiers shown above, containing falsified British battle plans. These documents were designed to mislead the Ottoman forces into believing that the main British attack would target Gaza, while the actual focus was on Beersheba, a strategically important location to the east.

The Ruse

This haversack was filled with an array of items to enhance its authenticity: a staff officer’s estimate complaining about the command’s focus on Gaza, reports on logistical challenges at Beersheba, an agenda for a meeting at Allenby’s headquarters, a telegram about a reconnaissance patrol, a map with arrows pointing to Gaza, a detailed operations order indicating a main attack on Gaza with an amphibious landing, rough notes about a wireless cipher, a large sum of pound banknotes, and personal letters, such as one from Meinertzhagen’s sister announcing a baby’s birth. Supporting deceptions included dummy wireless messages decipherable with a captured cipher code, a Desert Mounted Corps message complaining about the lost haversack, notices to subordinate units requesting its return, and patrols discarding sandwiches wrapped in a bogus operations order.

We have to stop here for a second. A solid filter to apply to intelligence operations, especially those reported to the public, is the presentation of ‘too perfect’ of evidence. In type of evidence, and especially in this case, in amount. Speed of the evidence being provided—and reported on—is also a reliable filter. Meaning, if there is the perfect type of evidence, a voluminous amount of evidence, and it is reported rapidly after the event (speaking more on today rather than in WW1) we should all be slowing down and asking questions. The type and volume of evidence in the Haversack Ruse suggest the information being simply handed to an organization for immediate distribution. Oftentimes the intent is to redirect attention to a target, from a target, or simply muddy the waters before deeper investigation(s) are carried out. All of the justifications can provide a type of cover for whatever intended operation is being carried out to the extent of the topic even getting buried as a ‘nothingburger’ thanks to the investigation looking legitimate and appearing to be legitimately concluded as well.

The execution of The Ruse involved a staff officer, ostensibly on a reconnaissance mission, being chased by a Turkish patrol, pretending to be wounded, and dropping the blood-stained haversack. This was intended to make the loss appear accidental, increasing the likelihood that the Ottomans would believe the contents. The operation was sanctioned by Allenby in September 1917, with the successful execution on October 10, 1917, by Arthur Neate, as later research confirmed.

The Operation

Initially, Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen was credited with both conceiving and executing the Haversack Ruse, a claim he reinforced in his diaries and later writings. His account suggested that he let the haversack fall into Ottoman hands, thereby bringing about the British victory in the Battle of Beersheba and Gaza. This narrative was popularized and even impressed figures like T.E. Lawrence, who mentioned it in "Seven Pillars of Wisdom", and was noted in the British Official History for its "extraordinary effect, hardly to be matched in the annals of modern war."

However, subsequent research has cast significant doubt on Meinertzhagen’s involvement. Brian Garfield’s 2007 book, "The Meinertzhagen Mystery: The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud," presents evidence that Meinertzhagen fabricated many of his exploits, including the Haversack Ruse. Garfield’s investigation, relying on independent sources from several countries, revealed that the idea was actually that of Lieutenant Colonel J.D. Belgrave, a member of Allenby’s general staff, and the rider who dropped the satchel was Arthur Neate, an active military intelligence officer at the time. Arthur Neate, unable to publicly refute Meinertzhagen’s claims in 1927 due to security norms, corrected the record in 1956 through a letter to the British public. Tragically, Lt. Col. Belgrave, the true author, was killed in action on June 13, 1918, and thus never had the opportunity to contradict Meinertzhagen’s account.

This controversy is further highlighted in sources like a Wikipedia page on Meinertzhagen, which states that his participation has been refuted, and a Haaretz article mentioning the ruse’s role in the Australian 4th Light Horse Brigade’s charge on Be’er Sheva, attributing success to surprise without delving into the authorship dispute.

The impact of the Haversack Ruse on the outcome of the campaign is a subject of debate. According to the Warfare History Network The Haversack Ruse impressed Lawrence Of Arabia, the ruse convinced German commander General Kress von Kressenstein that the main attack would be frontal from the south at Gaza, leading to Turkish deployment errors. This resulted in the capture of Gaza and Jerusalem, with significant Ottoman losses: 12,000 prisoners, 1,000 artillery pieces captured, and 25,000 Turkish casualties compared to 18,000 British casualties from October 31 to December 11, 1917. T.E. Lawrence credited Meinertzhagen for the conception and execution, adding to its legendary status.

However, the Wikipedia page and other sources suggest a more nuanced picture. Ottoman military leaders, led by Kress von Kressenstein, doubted the documents’ authenticity, with von Kressenstein later writing that he did not believe they were real, citing the timing after the rainy season. An account by Turkish Colonel Hussein Husni, Chief of Staff of the 7th Army, noted that Meinertzhagen’s German-sounding name added to suspicions, and no changes in Ottoman positions occurred, indicating no effect on decision-making. This suggests that while the ruse may have caused confusion, its direct influence on Ottoman strategy might have been limited.

Despite these doubts, the cumulative effect of the Haversack Ruse, combined with other deception measures like dummy wireless messages, likely contributed to the British success. The operation’s legacy is evident in its inspiration for later World War II deceptions, such as OPERATION MINCEMEAT, where a corpse was used to plant false information, and its depiction in popular culture, including the 1987 film "The Lighthorsemen" and scenes in "The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles."

Conclusion

The Haversack Ruse’s legacy extends beyond its immediate impact, influencing military strategy and deception operations in subsequent conflicts. Its mention in the British Official History and by figures like Lawrence of Arabia underscores its perceived importance, even if the exact contribution is debated. The controversy over Meinertzhagen’s claims highlights the challenges of historical accuracy, especially when relying on personal accounts, and serves as a cautionary tale about the fabrication of military exploits.

The Haversack Ruse was a pivotal deception operation in World War I, likely effective in its strategic goals despite some Ottoman skepticism. It serves as an example of the flavor of tactics and the lengths at which military intelligence operations are willing to go in order to achieve success—across a myriad of objectives.

Keep in mind that intelligence operations are never singularly focused, they involve immediate outcomes, 2nd+ order outcomes, changes in behavior and countermoves for further intel and data collection, and of course plausible deniability.

I look forward to sharing more on covert military operations so we may discuss how they have been adapted to today, including resources documenting proven evidence, beyond entertaining speculation.